Emotion Works _ What is it and how can I use it in my classroom/setting?

Emotion Works was developed by Claire Murray in Edinburgh and about 4 years ago I came across it on the internet. The first thing that caught my eye was the visual cogs. Thinking that this would be good for the pupils with autism that we support at Reachout ASC, we jumped on a train and attended a training day in Glasgow.

We ‘got it’ straight away. We were working to develop the emotional literacy and problem solving skills of our pupils and here was a resource that would enable us to do this better. We liked it because it was visual and structured. It broke down all the issues around emotions into manageable components and this gave us the chance to use it flexibly with pupils of all different ages and abilities. The pack and licence gave us everything we needed to get us started and we still find there is everything we need in that. The extras that Claire has developed are great too.

You can watch a short film ‘All about Emotion Works’ over on their website here Our Story – Emotion Works

At the heart of the Emotion Works Approach is a simple and versatile visual resource called ‘The Component Model of Emotion’. This colour-coded model identifies seven aspects of emotional knowledge and competence that work together to show how ’emotion works’.

In Primary School there are many opportunities to develop emotional literacy. I can see how a class teacher could use this in many lessons to explore characters in stories, poetry and topic work such as motives of key players in history. It would be good to develop many aspects of PSHE and RE. The literacy aspect works well to develop good writing and speaking. Children learn to develop their own understanding of what makes them work and how events, emotions, thoughts and behaviours work together. There are some fabulous examples of whole class learning on her website. You can find out more about their Literacy Programme and stimuli idea on their padlets here Emotion Works Literacy Padlets

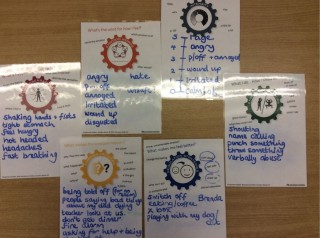

For us as autism specialist teachers, we often work with individuals or 1:1 with pupils. We use Emotion Works as a teaching tool to develop emotional literacy. This involves introducing emotion words (using the visual symbols that come with the pack) and helping the child identify events and ‘triggers’ that prompt these emotions. With some pupils with autism, this helps their memory and recall as well as connecting events to emotions. With other children we use Emotion Works to help with problem solving. We might start by identifying a problem, a situation or an emotion they are struggling with, and then work with a 4, 5 or 6 part model (depending on the child) to work out what the problem is about. We can work out what things are connected to the problem and then concentrate on the blue cog in trying to work out what the solution or support needed could be. This blue cog is our favouritie…”What makes me feel better?” is a good question to ask. What we love is that all this involves the child. They are listened to, they offer their own viewpoint and they are involved in choosing the strategies for change. There are plenty of visual resources in the Emotion Works pack to support those with poorer verbal language and the whole structure helps pupils with autism be able to process each part at a time and then see it together as a whole. Here is an example of one exploring the character of the troll and the Billy goat from Claire’s website.

Secondary Pupils.

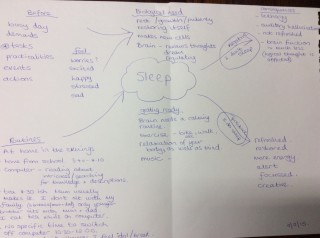

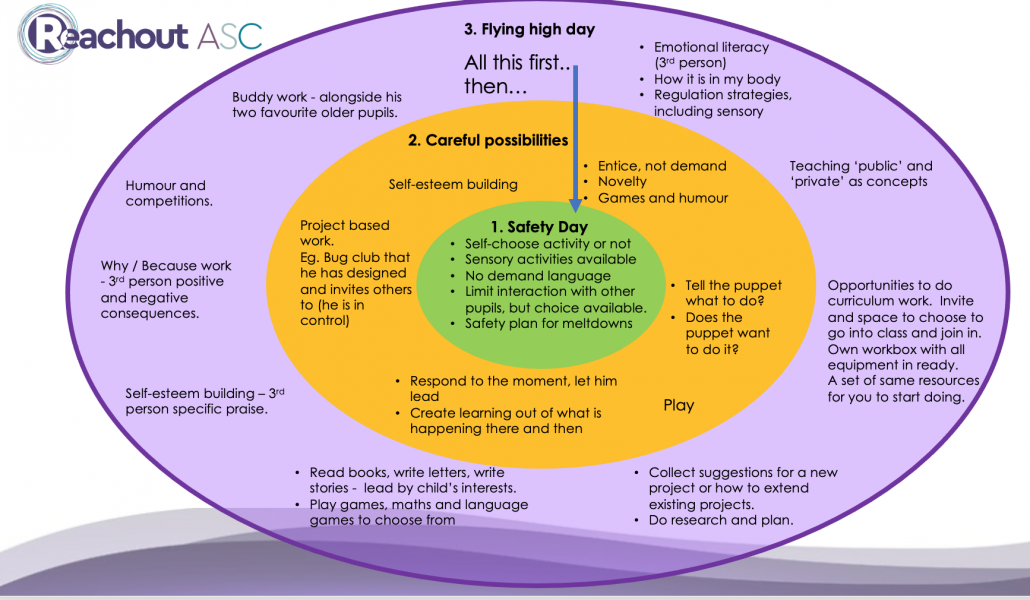

To be honest, we actually use Emotion Works more with secondary age pupils than with primary. That is mainly because we are not class teachers (if I was I’d be using it in many different lessons, as above). We have found that pupils with autism who have made it to secondary school are coping with many more stressful situations and problems that they ever had to at primary school. We are fortunate to work regularly with individuals (from weekly to monthly) and have time to work through issues, problems, challenges and emotions with them. We have used Emotion Works in group work and with individuals and the reason I am writing this post and inviting Claire Murray down to Lancashire to launch Emotion Works here, is because the response we get from nearly every pupil is amazing. Considering the difficulties pupils with autism often have in communicating and understanding different aspects of an event or emotion, we have seen that the respond to the visual structure of Emotion Works really well and the things they have been able to tell us wouldn’t have happened without this support. We develop a lot of the ideas into a bigger visual map (such as the one about sleep, below) and the two are then permanent visual supports for the pupil , their teachers and parents to remind them of what we have discussed and what they might like to do about it.

I think I need to give you some examples.

Preparing for a new situation

From moving up to Year 10 when the curriculum changes and GCSE pressure kicks in, to going on a school trip or being invited to a party, Emotion Works has enabled us to explore with the pupil how this might be making them feel, what effect that is having on them, and what they could do to manage the emotion and situation better. It can lead to a plan being made to help them deal with the new experience or a change in the way they are supported to enable more suitable support (for example changing from a TA in the classroom to a mentor type role to deal with the homework for GCSE). Mostly, it helps the SENCO, parent and teachers understand what the pupil really is dealing with rather than them assuming they know!

Understanding anxiety and anger

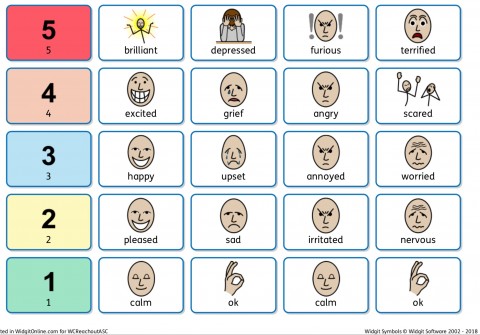

Anger and anxiety are big emotions. Having autism can make these bigger and more constant than for other pupils and understanding the role puberty can take in having these emotions is also important. Each pupil has very individual triggers and reactions to these emotions and it has been amazing to be able to explore these with them. It has worked as a small group (such as in the part example about anxiety with a group of girls with Asperger’s and the example about anger with a group of boys with ASD below). We have found the grey cog (intensity) particularly useful and sometimes link this to the “Five Point Scale” so that we can explore how they could recognise the earlier stages of the emotion and find regulation strategies. The purple cog (influences) was particularly good to explore next, as peer pressure and self esteem were other themes that came out of our discussion.

Restorative Practice

It happens occasionally that we arrive in school and there has been ‘an incident’. We sometimes find that exploring what happened, the triggers and the emotions can really help a pupil and their teachers understand the whole story. It often identifies where the key trigger was and helps us ask the pupil how we could restore relationships or order in a fair way. Mostly the pupil responds well because they feel they have been listened to, even if they might have been in the wrong. If someone else was in the wrong, or perceived to be, we can then work with the school and pupil to put things right. On more than one occasion it has helped us identify the early stages of bullying and deal with that. It has also helped us work with friends falling out and restore the friendship!

Teaching emotional literacy

We like all our pupils to develop emotional literacy at a level they can understand. This is an important aspect of our support for their mental health and wellbeing. Professor Tony Attwood says that most people with Asperger’s (and autism) don’t understand what ‘CALM’ actually is as they live with so much anxiety constantly in their lives. We have addressed this in all our work with children and young people from the early years to young adults in giving them the chance to explore what calm means and what other emotions drive their thoughts and behaviours. With many of our pupils we can do this using Emotion Works as our base and then concentrating on the blue cog, “What makes us feel better?” It is from this we use a variety of other resources to explore what actually does. It can be anxiety management, social stories, exercise and sports, sensory diets, jokes, special interests, developing friendships and other supportive relationships, ways to feel comfortable in social inclusion, learning about something new or a mixture of all these things.

Parents and other professionals

I think this resource could really be used by parents and I can see lots of possibilities for families of children with ASC to develop emotional communication. Starting young, one or two of the cogs can be explored and more introduced as the child gets older or more able to develop those concepts. Teenagers may not want to talk to their parents but this may give a framework for communication in the teenage years with a no-blame and listening approach. I’d use it to teach about drugs, alcohol and sexual attraction, consent and other big relationship and life issues.

Professional from CAMHS, hospitals and many others could use this model to explore emotional and physical difficulties. I like the idea of doctors using this to explore what might be wrong when a person with autism is sick and show them clearly what could make them feel better.

Training enquiries email: https://www.emotionworks.org.uk/contact/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.