What makes transition work for Autistic pupils?

Autistic pupils can find everyday transitions difficult, as well as the major transitions that happen. The reasons can include:

- Not being told what the change will involve,

- What will be expected of them,

- How long it’s going to last,

- Perceived or real sensory challenges,

- Not being given time enough to process the changes or enough information to do so

- Being so engrossed and comfortable in what they are doing that they cannot seem to switch attention and move to somewhere else,

Transitions can cause a lot of anxiety.

If you’re involved in supporting children with every day transitions and often a visual timetable used correctly (see my blog post here) can help enormously and give the pupil some interaction and choices when appropriate. Giving them time to process and information about what to expect is important. An example is a child who hated lining up because he didn’t know where he was going. He did everything he can to avoid lining up, such as hitting others in the hope he’d be made to stay behind. For him, we worked with him to ask “Where are we going?”; So he didn’t have to rely on an adult telling him and he felt less anxious and more in control.

But what about the major transition of moving to the next class or from Primary to Secondary School…

When it goes well.

Transitions to a new class in the same school

The big transitions happen in September as the child moves to a new class in Primary or a new school as in starting secondary school. For class to class transition, all the following principles apply, and I think it’s really important to help the child see what will be the SAME as well as different. It’s how our brains cope with change. We make connections with what is familiar to us, drawing on our past experiences and looking for connections. We need to support autistic pupils in the same way. I have written a social story booklet you can use here

Transition to secondary school

I’m pleased to see that many secondary schools are getting better at transition, particularly for their SEND pupils. I say some, because others have not been so good. I’ll come to that later. When it works well, transition:

- Starts as early as year 4. Parents and the school should start to have the conversation of what is the next step for the child. Parents need time to emotionally process the fact that their child is going to be making a major move. They will feel nervous too. Starting early means they have time to look around, do the research and be ready for a more formal transition meeting in Y5.

- A transition plan is put in place. Some good resources for this can be found – I love the resources below, do take a look. They are really helpful in supporting parents and schools to work together. Often the secondary school won’t get involved until the child has been offered a definite place. DON’T PANIC. There is still plenty of time for them to do a good transition.

- The autistic pupil is helped to prepare, gently, positively and with the right support for them. I often start with a timeline at the start of Y6. This plots out the whole year and key events, including secondary applications, notifications of places, holidays, trips, open evenings and trips to secondary schools and so on. We use different coloured pens and are able to add other things that come up. This works better than a calendar for most, as they can see the whole year and how much time is between each event.

- The pupil is familiar with their new class / school before they make the move. This should take as many visits as the child needs, at different times. For example, the first visit during lesson time when all the classes are in their rooms and the corridors are quiet. Extra visits might be made to familiarise the pupil with the dining hall, where the lockers and toilets are and where they can go for help, or quiet places to go at break times.

- The pupil has had the chance to meet key people who will be there to support them on their first day. Photos may be taken to remind them over the summer holidays.

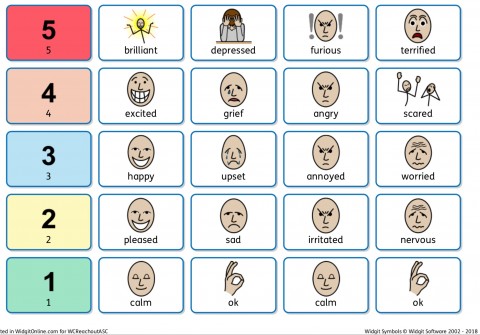

- The pupil has someone they can discuss their worries and fears with. They have the opportunity to chat in a group with peers/friends so that they all know they have similar challenges ahead and so that they can help each other with suggestions.

- Relevant and up-to-date paper work has been prepared and passed on to the SENCO of the receiving school. This does not always happen.

- The Primary school begin to help the pupil learn to work with other adults, especially if they’ve had a long term TA, it is unusual and probably not possible for a pupil to have the same 1:1 all the time at secondary school.

- The pupil has some input and contribution to their transition. This may include choosing dates and activities to do on visits, taking their own photos or video around the new school, choosing their new school bag, preparing a place to do home work.(Advice for pupils who are struggling with anxiety or unable to do homework)

- Parents feel informed, reassured and that they know who to contact when issues or questions arise.

- The receiving teachers/school has had or is planning Autism training so that staff understand the spectrum and range of strengths and support needs in autism and how to help the pupil(s) that they are welcoming into their school or class. You can start with my Ten Top Tips for Secondary teachers.

Schools who do good and successful transitions are flexible, involve the children and reassure parents. One school I work with has a very successful summer school that has help numerous Autistic and SEND pupils to settle in well once they start Y7. This school also has a dedicated Y7 support teacher, who doesn’t teach and works with all the pupils to deal with issues as soon as they come up right throughout their first year of secondary school.

When it goes badly.

Sometimes the move to a new class or school goes wrong for the child. Often ending in permanent exclusion or at best, a lot of hard work to claw back the progress that should have been made. Sometimes this is the time a specialist teacher is called for, it’s not a good point to start. We would much rather help at the actual transition stage and avoid some of these mistakes. In the end, it can destroy a child’s confidence, their education chances and mental health. Having had to pick up the pieces of failed transitions in the past, it’s always the child who suffers most. I do a lot of work with our county’s Primary and Secondary PRUs. The PRUs I work with will agree with me. They are getting more and more autistic pupils who have been excluded from mainstream schools and many could have been supported better.

Bad transitions happen when:

- No one bothers to put a plan in place.

- The pupil is not given any preparation that is suitable for them.

- Parents are not consulted and there is poor communication between the schools and home.

- The pupil is ‘forced’ to move through exclusion or a hurriedly ‘managed move’.

- Communication between schools is poor or non-existent.

- Paperwork is not passed on so receiving school know nothing about the child’s needs.

- A ‘no-excuses’ approach to behaviour is rigidly enforced from day 1 and child learns to fail straight away without any support to achieve good behaviour.

- Staff don’t have any Autism training and think the pupils are ‘doing it on purpose’ (whatever ‘it’ may be).

- Staff think that ‘kids like that’ shouldn’t be in their school.

I hate having to write this part. Thankfully we work with some fantastic schools who get transition right. It’s the stories we hear from other sources and when children have come to them on ‘managed moves’ or without the right support that we have realised that these things actually happen. Parents then have a fight to help their son or daughter settle into a secondary school that doesn’t seem to want them.

If you are a parent, SENCO or teacher starting to think about a move to secondary school, or even to the next class then here are some great resources. Good planning and preparation that involves the pupil will pay off generously in years to come.

This is our free course with advice for schools, parents and pupils on transition which was produced in lockdown but has lots of still relevant advice.

https://www.schudio.tv/courses/the-big-transitions-for-autistic-and-send-pupils-after-lockdown

https://www.schudio.tv/courses/supporting-primary-to-high-school-transition-for-parents-students

National Autistic Society advice on transition

And here is our free booklet that can be filled in about going to secondary school

https://reachoutasc.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/ReachoutASCtransitiontoSecondaryschoolbooklet.pdf

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.