Building good relationships with parents of autistic children.

“We don’t see that behaviour at school”

“He’s doing it on purpose, he gets away with it at home”

“There’s no structure at home, you know”

These are some of the comments we might hear in the staff room. It certainly not from all teachers or teaching staff, and it’s certainly not heard in many schools I work with. But during training discussions or the occasional, off-the-cuff remark, there is an underlying search to find blame for an autistic child’s behaviour. Especially when they have meltdowns, in school or at home. Or if the behaviour is a controlling or manipulating behaviour. No teacher likes to think a child is trying to manipulate them. We are human after all.

Parents of autistic children are as human as the rest of us. Some are so overwhelmed they don’t know what to do, some are given a diagnosis and then dropped into a black hole of nothing – no advice, no courses, no strategies, no support. Some are dealing with their own difficulties, some families are broken and dealing with issues beyond what we may know. Some families are trying everything they can, do all the research, attend all the courses and know their child’s needs inside out.We have to start with a basis that parents love their autistic child, want the best for them and need support and understanding from the school system to help them travel this journey with a child with additional needs. No matter what their circumstances the very first barrier they come up against is judgement. The SEND system is complex and weighted against getting sometimes just the basic resources in place for their child.

Sometimes, as we discuss behaviour on a course I am presenting, the teaching staff want to know how much of a child’s behaviour is because the parent isn’t doing a good job. It can sound like a need to explain why they are finding the child’s behaviour difficult to control, manage or change. Obviously I do explain how supporting a child who has high anxiety, sensory overloads, constant need for routines and familiarity, and difficulty with social relationships (including the interactions with family members) as well as trying to develop a safe, loving, constant, predictable and supportive life for their child is just as much a learning journey for the parent as it is for the school. We only have the child in our class for one year in a primary school or a few lessons a week if at secondary school. The parent has the child’s whole life to think of and that will be their focus. They will be worried that their needs will not be met. They will worry about admitting that they can’t help their child with their meltdown’s or other behaviours. They will worry about them growing up and needing care when they aren’t there. They will worry whether they could ever get married, have children, hold down a job.

And school is so often a battleground. Parents have to fight to get their child’s needs met. They have to try to understand this complex SEND process and the tons of paperwork, appointments and in-depth questioning of their family life just to get some help for their child at school. (Some parents know the SEND law far better than schools, because they have had to). It can take YEARS just to get a basic assessment and diagnostic services are hugely underfunded and the waiting lists are LONG. In the meantime, the child still has needs to be met and we have to be careful not to refuse to look at what those needs might be in school because there is no diagnosis yet. As teachers we are bound by the law to do Quality First Teaching for all, and to implement the Graduated Approach in assessing, planning, doing and reviewing the support for a child with SEND.

Parents are well aware that their autistic child is often under great stress just to manage the social, communication and curriculum demands of each day. And yes, occasionally, some parents will be getting it wrong. But who are we to use that against them? It’s our job as teachers to do all we can to make school work for an autistic child, and where possible work with parents in a professional and positive way. Every bit of effort you put into building a positive relationship with parents (even those who start off very defensive or even aggressive) will pay off and can help the child in ways you couldn’t do without it.

So here are my top tips for working with parents.

- Communicate. Communicate. Communicate. Plan this so it is manageable and set an agenda for chats if you need to. I encourage schools to set a regular time to talk to parents about what their child is doing in school. For example, every Thursday after school for ½ hour. Or every 2 weeks for so many minutes. Whatever time you can make or is available. Email each other, but put safe boundaries in for you both to understand. This can help prevent parents and teachers or TAs getting frustrated about when they can meet up and prevent getting into the habit of meeting EVERY afternoon which isn’t sustainable. Some parents like a list of points they can prepare for, others just want to ‘offload’. Remember you can’t solve all the problems they are having. Often all they need is for someone to listen. If you have agreed the timescale before-hand, make sure you give your full attention to them for that time you have promised.

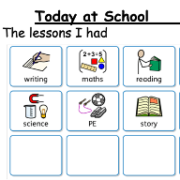

- When you talk to parents don’t make it a list of everything the child has done wrong. Tell them important news about what’s happening in school, what their child has done well and celebrate excellent moments. Many autistic children do not tell their parents anything about school. School is school, home is home. Some are too exhausted to recall what has been for them a stressful day, even when things have gone well. You could use our visual home – school sheet.

- Remember that parents do know their children best. Ask, listen and learn from them.

- Consider using a home-school diary. Share bullet points about the events of the day and a general overview of the child’s positive moments. If the child is non-verbal you could use a picture based record You could use our visual home – school sheet.

- Parents do need to know about serious incidents but these should be spoken about by phone or face to face rather than third hand (from other parents) or via the home-school book.

- Invite parents to contribute the targets in the child’s IEP. We used to have ways the parent could (if they wanted) generalise the target at home. This was particularly useful for communication, social and independence targets.

- Find out where they can get extra help / support for issues that are beyond school. A list of local support groups for a variety of SEND needs can be put on the schools website.

I’m sure there are many more ideas. Please do share your good practice in the comments. There’s too many parents of children with SEND /Autism who find school communication frustrating, patronising and difficult. It doesn’t have to be. And if it does break down because there is a parent who doesn’t want to work with school, then we stay professional and still do the right thing. It’s our job.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.