Preparing an autism friendly secondary classroom

As I promised, here are my tips for secondary teachers getting ready for the next school year. There are likely to be a number of autistic students or other SEND needs coming into your classes this year and I want to share some of the tips and advice that I would usually pass on to secondary teachers.

Emma, Sarah, Alison and I work with around ten secondary schools and our support looks very different from the work we do with primaries. The differences in the way a secondary school works brings up additional challenges for the school SENCO and for individual teachers.

Firstly, the movement between lessons, having up to six different teachers each day and the responsibility of being organised, on time for lessons and doing homework are major challenges for autistic / SEND pupils. On top of that is the minefield of social relationships, especially in Year 7 when children are meeting lots of new children from different feeder primaries and everyone is working out new relationships and friendships. I’m not going to go into all the challenges and issues in this blog, but give teachers some tips on how they can make their classrooms and lessons autism/SEND friendly and a little bit of advice for a whole school approach that really makes a huge difference.

“Daily Transitions

“I was really scared of the corridors. All the noise and so many people made my brain scream. I couldn’t focus on where I was going and so I hid until everyone had gone. I was always late for lessons.” Girl with ASC, Year 7.

Once an autistic student has started at a secondary school it is common for them to take longer than most students to be able to settle into the routines of changing rooms between lessons and coping with the different teachers that they meet throughout the day. Some students will need escorting (by teaching assistant or other students) to each class for some time. Others may benefit from being allowed to leave each class early to avoid the sensory overload of the corridors and travel to their next class in the quieter corridors. In Year 7 a buddy system may be set up so that autistic students are not left behind when a class moves on.

Teachers should be aware that it can take some time for the student to adjust to their voice, subject matter and style when they have just come from another teacher who may be very different. Subject teachers can support this by

- Having a seating plan and allowing the autistic student to choose where they sit (where they are comfortable, with a friend, can see the main focus of the lesson, get to the door easily).

- Giving the autistic student time to settle, longer than other students, speaking to them kindly to remind them where they are and which subject they are now doing.

- Get to know the autistic student, talk to them about their interests and use this as a basis for your relationship. They will appreciate you for it.”

This is an excerpt from my book “How to Support students with Autism Spectrum Condition in Secondary School” page 23 published by LDA

The Classroom environment

- Each subject teacher will want to make their classroom welcoming and most of all, functional for a classes of different year groups coming into their room each day. Displays tend to be less of an issue for secondary rooms but clutter can be as much a problem for children who are visually distracted and find it hard to focus as in any classroom.

- Have a clear space around your whiteboard. Enables students to focus solely on the screen / board. You could put key vocabulary words for the topic on the wall at the side of the whiteboard for those whose attention may wander slightly. You’d have to change this for each year group but if you have them on Velcro they can be easily changed.

- Display visual pictures with key vocabulary. This helps students remember and understand if they miss or don’t understand verbal information.

- Keep class rules simple. Most rules can be summed up in 2 points: Be safe. Be kind.

- Have a seating plan and keep to it. It really is worth allowing autistic/SEND pupils have some say in where they sit. For example, having to look over the tops of other people’s heads can mean accessing what is on the board more difficult for them.

- Suggest disorganised students colour code their timetable with the colour of the subject exercise books. It might help them bring the right book to your lesson.

- It is likely an autistic student or SEND will struggle to have the right equipment. If that’s going to be likely in your class, have a spare set for them, kept in class and that they can access without making a fuss at the beginning of the lesson.

Accessing lessons

- Copying off the board takes a lot of switching attention which can be so difficult for Autistic/SEND students. Plan to give out printed copies of the text and ask students to highlight key words or important points, it is much more effective.

- For those who find writing difficult; find other ways of recording what they know, so they can vary how they record their work. For example, most computers have speech to text (they can try this for homework first), or typing it on a laptop or even dictating to a recording device. Diagrams, mind maps, power point, photos and other visual recording can help some pupils.

- Remember your autistic students could be the best student you have, they may know as much as you do about your subject and be extremely bright. But that could mean they are easily bored and don’t get the point of when you need to go over information for other students.

- Printing off homework on sticky labels and giving these out means homework is always accurately recorded in their planners. If you have an online homework system, make sure the autistic/SEND student (and their parents) know how it works and can access it.

- A pupil passport is a great way to give every subject teacher the key information about each student; read it and plan the strategies into your whole class teaching.

- Use TAs wisely. The hardest thing is finding time to talk to them but if you can make time you will reap the benefits. (This is easier when a TA is based in a department, make sure they are part of departmental meetings). Have a look at this publication from the Education Endowment Foundation for tips on using TAs better.

- Group work is a common complaint from my autistic students, they hate it! I suggest subject teachers plan structured paired work to help all students work collaboratively, and build up to group work. A structure, with well-defined roles works best. See our blog on group work.

Parents

- Set up an email link with parents. Some secondaries have good parent communication systems in place, others have yet to get there. But as a subject leader try to communicate directly with parents about their child in the first half term. They will want to know how they are settling in. You could send a postcard. Ask them if there is anything they can share that will help you teach their child in your subject. It maybe having a spare PE kit in school will be vital for them actually having PE kit. It may be that you need to email the ingredients for cooking directly to the parents to ensure that the student will have what they need. English teachers might use a book they really like.

- Pass on any information (especially good things) to the SENCO or pastoral leader whoever is the person who might speak to parents the most. Having up to date information to hand will make their job much easier.

- Talk to other subject teachers and the SENCO before you contact parents about a behaviour or other problem. It will be important to know if there is a similar problem in other subjects and if there are any particular links. For example, it could be a break time issue that impacts on your lesson just after break and other subjects find the same on the other days.

Behaviour

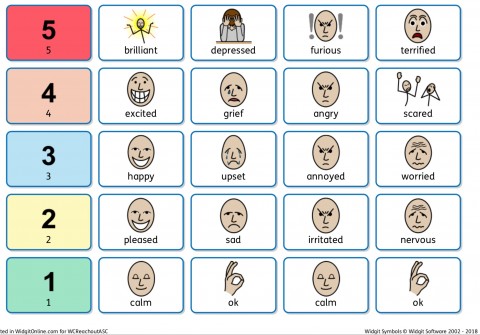

- School is often overwhelming for autistic/SEND students. Be aware of sensory sensitivities and needs. The student may need a break occasionally. A time-out card can help them do this without fuss. They can be taught how to use this to calm down and return to the class.

- Low level disruptions are often attempts to communicate. Students who find it hard to follow or join in conversation often act loudly or silly because that gets feedback and acceptance from their peers. Structured paired work and teaching conversation / public speaking skills can help the whole class.

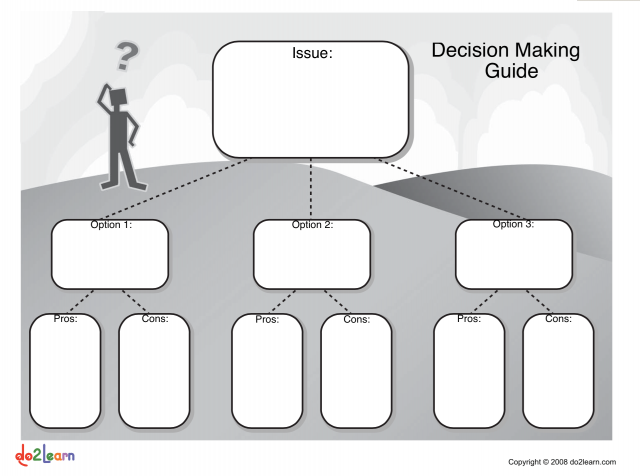

- Other low level disruption occurs when a student doesn’t understand what they have to do or feel they can’t do it. They might be unable to ask for help, or try to distract you from asking them what they have done. Don’t just explain using the same words – a task may need breaking into smaller chunks and explaining more clearly.

- Be aware of those who find being the centre of attention too much to cope with. Give them chance to answer questions through writing answers down on a whiteboard, talk to them individually and don’t point out anything they are doing in front of the whole class.

- Talk to your autistic/ SEND students about what they are interested in. Especially if they have a topic they like to talk about a lot. They will really appreciate you taking a few minutes every now and again to chat to them about it. Get to know them and what makes them tick. All children work well for the teachers they know like them.

- Students with autism can be very honest. I was once told I stank because I’d put perfume on that day. Don’t take anything personally. If they are shouting obscenities at you they are VERY stressed and you should use your skill to help them not get into verbal combat with them.

- Know who you can call for help. Prevention is better than reaction but if you are in a position where the student can’t cope with your lesson and has become angry or upset, know what the plan is and follow it carefully. It works best when every teacher has a visual card with the plan on it that they can show the student and so reduce verbal language which causes more stress.

- Have high expectations of behaviour, but know that autistic / SEND students often need support to achieve those standards. Writing a clear explanation down of what you want, rather than telling off for what they are doing wrong works much better than lots of nagging. Believe me!

There’s lots and lots of other advice I could give but not much space in this blog. Here is the link to the ten top tips sheet that can be printed and given to secondary teachers. . In my Secondary book I have put a lot more about transitions, accessing the curriculum (more subject specific information), behaviour support, social support, puberty and SRE as well as exam support. It is aimed at non-autism-specialist teachers but SENCOs will find it really useful too. It’s a handbook to dip in and out of. (Get the sticky tabs ready.) Hope you might think of buying it!

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.