Supporting Children with Autism at Playtimes.

Playtimes can be tricky for autistic children ….

- It’s unstructured time – which some like (no demands) and others hate (don’t know what to do or how to fill the time).

- It’s a sensory overload, – which some love because they are sensory seekers and need the movement and sensory stimulation and others hate because the sights, sounds, smells, noise, weather, movement, touch and space of a playground hurts them.

- It’s socially demanding – which most don’t like because there’s a lot to take in, children are moving and talking and shouting and playing and coming at them from all directions. They might not know where to start to even ask to play, and possibly no-one asks them to play.

- The rules keep changing – so when they thought they were playing one game, someone changes it to another, just like that, and they can’t keep up and are left behind, or get angry because you changed the rules and that is stressful beyond words.

- There’s no place to escape – some will wander, trying to find their own bit of space where they can just be on their own for a bit. Others will invent their own worlds to escape to so the noise and mess around them can be shut out.

- It’s scary and it’s easy to feel angry – Children are running, screaming and pushing. How do they know when to stop? Imagine a child with autism who is frightened, because they don’t know how to stop themselves or join in without getting it wrong. Hitting out at others is just getting them out of the way…or attempting to join in when you can’t communicate so well.

- It’s exhausting – even though a child with autism may look like they’re doing ok and joining in, the effort is exhausting. You notice it when they come back into class, especially in the afternoon. Or maybe it’s their parents who find out when they go home and it all comes out. They’ve used up all their spoons.

“Whilst it is true that autistic people can struggle to process and understand the intentions of others within social interactions, when one listens to the accounts of autistic people, one could say such problems are in both directions.” Dr Damian Milton – The Double Empathy Problem

Here are some ways you can help.

- Build in some structure – work with the child to find ways of structuring the playtimes. It could be 3 x 5 minute activities. It could be a set of game bags that they choose one to play with a friend. (Jenny Mossley’s playtime books have some great ideas about these).

- Give them some time to be alone – inside if necessary. Some children need this. Don’t force them to be sociable and interact with others if it is causing them so much stress. They might like to just do nothing particular, a sensory calming activity, or to play with some of their favourite toys. They might like to do certain jobs such as tidying the library or sorting out the Lego. They might find this helps them cope better with the rest of the day.

- Assess how anxious playtime is making the child – This will indicate what you may need to do. If anxiety is high, don’t ignore it. Staying in, or letting them have a break from interaction may be the best thing you can do to help them regulate their anxiety. For others, a TA to support them might be what they need and that makes them feel safer and happier. For others, supporting them and the other children to play together well might be what they need.

- Involve Sensory Movement Activities – Or any sensory activities that the child may use and is part of their sensory diet, if they have one. Get other children to join in. For example, a sensory seeking child may love to have a group of children doing a sensory circuit with them on the playground equipment.

- Think carefully before using a TA to supervise 1:1 at playtimes – Why are they there? What is their role? Is it to help the child learn skills they want to learn, or to prompt them about behaviour? Is the TA going to be spending the time telling the child off, or modelling to other children how to interact well with the child?

- Have a buddy group – This works more informally than a Circle of Friends. It depends on the child and their desire to have people they can play with. Ideally a buddy group is supported through sessions where they work out what they all like to play, discuss what to do if someone doesn’t want to play and how to help each other to have an enjoyable playtime.It can work well with high school students too.

- Have break time clubs – Those that cover the particular interests of the children with ASC work well. In primary schools, I have helped set up dinosaur, Mario and Lego clubs; games clubs and computer clubs. In high schools, I’ve seen ‘Snack and Chat’ groups; Minecraft, Warhammer, craft and science clubs.

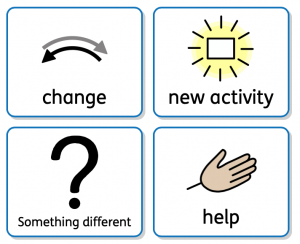

- Teach how to be a social detective – This helps children learn to understand what is going on, how to join in with what they would like to and learn to interact with their friends. I do a lot of social skills teaching but it isn’t about trying to make the autistic child ‘fit in’ but is about teaching a group of children how to accept and get along with each other. We often do this through social stories that explain and games to practice how we work together. It helps the non-autistic children just as much because all children need to develop the skills and knowledge about how to interact successfully with a wide range of people. That’s why listening to each other is a big part of that.

WE’ve developed a whole set of prepared resources you can buy to help you teach being a Social Detective – see here.

Part of the resistance to this level of support at playtimes comes from lack of staffing available to set up and implement/supervise these interventions. But we also forget that we have staff, especially at lunch times that could be trained up to work with and support children with ASC. Welfare staff are often the last to be invited to training and meetings about ASC or the children they spend an hour with every day. Investment in welfare staff training can be very effective.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.