Have you noticed? Girls on the Autistic Spectrum.

I’ve recently worked with some schools to assess and apply for an autism diagnosis for girls. What was interesting was that each school had had some autism training from me and began to realise that these girls showed some of the same characteristics that I had spoken about. For some, the diagnosis was straight forward. However, for at least one, it was not so. (continued below…)

The problem can be that not all doctors who do diagnostic assessments are as up to date as they should be. They don’t realise that the diagnostic assessments themselves are weighted to the male autism characteristics and that research is still developing that looks at the female autism profile. (Gould and Ashton-Smith, 2011).

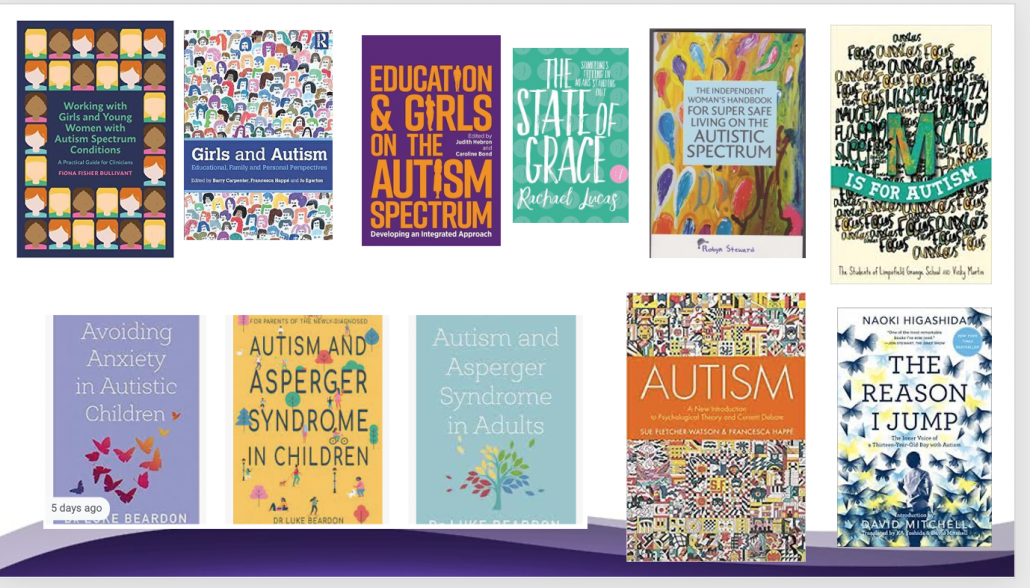

Our awareness of this has been helped by female autistic adults, who are themselves seeking diagnosis and then writing about it. So, authors like Liane Willey-Holliday, Tanya Marshall and Ann Memmott are writing blogs, books and pressing for more research to be done. We had the ITV programme “Girls with Autism” which aired in July 2019 and the book released by the Limpsfield Grange school in Surrey. A quick internet search calls up countless articles and information about girls on the spectrum.

But what do you really need to know. Here’s a short outline of SOME of the features to look out for in girls, and if you think a girl in your class may be on the autism spectrum, then seek advice from an autism specialist teacher or an Educational Psychologist, who will be able to guide you and parents through the process. But look out for the boys who are masking too as there is no female autism type, it’s just that we have not been looking for the children who mask.

I did a free webinar about autistic girls with the lovely Jodie Smitten who wrote a book with her daughter (https://www.amazon.co.uk/Secret-Life-Rose-Inside-Autistic/dp/B08WS2VQYB)

and the webinar can be watched here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LZE6XGOvdJo

Communication

- Boys are often identified by their behaviour. When they cannot find the words to use, they use actions to make their needs known or in reaction to distressing situations. Whilst girls can also do this, often girls on the autistic spectrum can be more passive. They may internalize their distress and be more vulnerable to mental health issues. They may be withdrawn or ‘moody’ or just ignore the demands, rather than challenge them.

- Girls may be extreme people pleasers or have no regard for the hierarchy of authority in school so can be seen as cheeky or rude, when they are just stating facts. Girls, like boys, can take language literally and so misunderstanding and confusion prevents them really ‘getting’ what is going on around them or what the teacher really means. Girls can also be incredibly articulate and clever in certain subjects.

- If an autistic girl gets by by imitating the social behaviours of those around her she may not be able to discriminate what are appropriate and what behaviours are not.

Social Communication and Interaction

- Autistic girls can seem more socially active, but they can want to dominate and be in control of the friendship group or cope by imitating the social behaviour of a group. This is often because it is the only way they can manage that situation. Often they cannot cope with jokes, teasing and communication breakdowns. They may be moody, withdrawn, and become distressed when things are difficult for them. On the other hand, they may seem to always be on their own, or on the edge of a group, not really knowing how to join in. One girl said to me, “I didn’t know if someone was my friend until they tell me they are. I knew someone for a year and when they asked me to go to their house after school, I had to ask them if that meant we were friends.”

- Autistic girls can ‘feel’ intensely. One thing can be intense shame when they don’t get something right, especially socially. They cannot often tell the difference between a small social mistake, something that everyone else would just brush off and move on, or a big mistake that marks you out as odd. Consequently, a lot of stress an awkwardness can be felt when they are in any classroom groups or social situations.

Social Imagination / Flexibility of Thought

- Play can seem very imaginative and autistic girls can lose themselves intensely in books and characters. The play however, can be very strict and controlled. For example, a doll is called a name, given a character and nothing can change that identity once it has been assigned. The special interests the girl has can be seemingly usual interests for girls, such as in ponies or celebrities, and they can become very intense and all-consuming and younger interests can still be present in adolescence. They can be creative and very imaginative and some say they would have preferred to live in their own imaginary worlds which were more predictable and interesting than the real world. Rosie King says this in her video.

- Autistic girls can have the same difficulties with lack of organisation and planning as autistic boys might do. They may have also become organisers who need to know where everything is, or they become very distressed. Change and new situations will also be difficult and girls can be as likely as boys to exhibit characteristics of PDA (Pathological Demand Avoidance).

- Autistic girls can be fun, talented, clever, and have lots of potential to make a great contribution to the world…Just like the boys!

Sensory

- Sensory issues and dealing with a busy, noisy, smelly, confusing world can be the most stressful thing that an autistic girl or boy has to deal with.If you want to know what it is like, watch this clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IcS2VUoe12M

To encourage you, one girl, in year 5 who received her diagnosis was extremely relieved. She and her family read all they could about it and she initially began talking about it all the time, often using it as an excuse. As we spent time with her to help her come to terms with her diagnosis, we looked at lots of positive role models and she asked if she could make a presentation about ASC to show her class,

“because then they might understand me and like me.”

It did indeed help her classmates understand her, and enabled friendships that had previously been disintegrating, start again and rebuild. that’s not it, not a ‘happy ever after’ ending and everything is sorted. This girl is now in Year 6 and likely to be going to a different high school from her friends. We are working with her and will work with her new school to do the best transition we can but the challenges she will face will be greater than her peers and I only can hope she receives the right support throughout her secondary years.

Here are just some of the great books that can help us understand autistic people in that wider spectrum.

References

- https://senmagazine.co.uk/articles/articles/senarticles/is-autism-different-for-girls

- Gould, J. and Ashton-Smith, J. (May 2011) Missed diagnosis or misdiagnosis? Girls and women on the autism spectrum, Good Autism Practice, Vol. 12 No. 1 p 34-41.

- http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2009/apr/12/autism-aspergers-girls?utm_content=bufferf7dc8&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer (Doctors failing to spot Asperger’s in Girls)

Twitter: Follow @TaniaAMarshall @Autism_Women @curlyhairedalis @ResearchAutism @AutisticGirls_ @CarlyJonesMBE @AnnMemmott @SwanAutism

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.