Autism and Christmas – Teachers are you ready?

Ok teachers this is THE half term when I get so many more emails about autistic pupils in school and their behaviour. I wanted to warn you all and help you get ready, but not for the challenging behaviour, no, it’s supporting your autistic pupils at this time of year that I want to help you with so that the chances of their behaviour changing is lessened.

Of course, the culprit, the trigger for behaviour at this time of year is most likely to be Christmas, not Christmas itself, but the way we DO Christmas.

This is what happens in most primary schools…

When we are talking about behaviour changes please remember that not all autistic pupils will have challenging behaviours when they are overwhelmed – they may just as easily have withdrawn behaviour and become very quiet or unusually tired all the time. Please watch out for the particular signs of stress in the child you teach.

THE SCHOOL NATIVITY OR PLAY

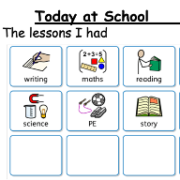

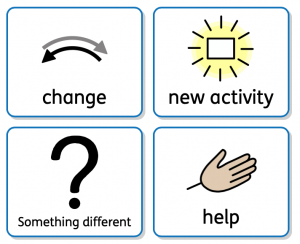

Have you started this yet? In the next few weeks; schools will be starting to introduce and practice for whatever Christmas play or carol service they put on. The usual routine will begin to change as practices take the place of PE (we’ve got the hall booked anyway) and other lessons. Singing, performing, dressing up, CHANGE can all be overwhelming for an autistic child. But by far the most unsettling thing or many of them is the constant, unpredictable changes to the timetable. A spontaneous play practice might be exciting for many of the class but for an autistic child it can be a nightmare.

What to do:

- Write a social story about what the play is about, why you are doing it and what their part in it is.

- Make sure that you have a ‘play practice’ symbol on their visual timetable.

- Speak to parents about how they help their child cope with Christmas and what tips they may have for supporting and/or involving their child.

- If they cannot cope with lots of sitting around and waiting as the play is practiced, then provide a box of activities that are linked to their special interests and let them take it into the hall to play with in a quiet corner.

- Do what you can to help them be able to take part, then always prepare them for anything new. Show them costumes beforehand and allow them time to get used to each different thing.

- Find any way possible for the child to be part of it. They could have a role they choose themselves, or be in charge of prompting other actors, a role in arranging the music or managing the CD player, be the one who sorts out and gives out costumes, in charge of lighting, or sitting somewhere comfortable, doing something they feel comfortable with, but is included in the performance. One child who loved dancing was given the role of the star and danced across the stage to her favourite music as the Wise Men followed.

- Be realistic about evening performances and don’t insist the autistic child should come if it is too much for them. Try to make sure parents have one successful performance to attend than two or more stressful ones.

Parents have told me how heartbreaking it is to be told that their child can’t do the Christmas Play. It’s usually said in a way that makes it sound like it would be too much for the child. But if we could just make some accommodations, then the majority of autistic children can be included. I can’t tell you how much this would mean to parents. And make sure the child is named on the programme and is photographed with the whole class.

And be extra nice in saving the child’s parents a seat at the performance. Ask them where they’d like to sit and make them feel it’s an honour to have them there. You will do something so small to you but so huge to parents that they will never forget your kindness.

THE DECORATIONS

You might think it’s exciting for all the children when you stay late at school one Friday night to put up all the hand-made decorations the children have been making for weeks so that you can hear their gasps of amazement when they walk through the doors on the Monday morning. But for an autistic child, you will have completely and unexpectedly changed their whole environment and that will cause them a great shock and anxiety. I have known many autistic children flatly refuse to go into school because the decorations were put up suddenly, or there was a Christmas tree by the door they go into school, and others who have had meltdowns because they cannot cope with the sensory overload.

What to do:

- Write a social story to explain why we make and display decorations at Christmas.

- Cut down on the amount of decorations you make. You really don’t have to do all of them. Try to keep the classroom tidy.

- Involve the autistic child in deciding where the decorations should go and try to have one or two decoration-free areas they can go to if overwhelmed.

- Involve the autistic child in decorating the school Christmas tree and have some say in where it should go.

THE CRAFT

We go craft crazy in Primary schools at Christmas. Glitter comes in huge tubs and boy do we use it liberally! But glue, glitter, many competing textures, shiny paper can be a big sensory distraction or overload for some autistic children which can send them into sensory overload or meltdown. (BTW – I love glitter but I’m really aware of the effect it may have on autistic children).

What to do:

- Slow down! It’s better to do one or two things well rather than lots of hurried, half-finished projects that get left around the room in a mess.

- Go with what the autistic child is interested in. For example, if they like Lego, let them make a Lego Christmas tree, scene or angel. Take a photo and put that on their Christmas card, calendar and if necessary, even every craft project if that makes it accessible to them.

- Don’t insist the autistic child must do the craft. They may need to do something that is connected to their regular routine instead. For example, if it’s usually a maths lesson, let them do maths if that helps them stay calm.

THE CHRISTMAS PARTY

More sensory overload! Different clothes, loud music, unstructured event, everything and everybody looking different. Food, sweets, sometimes an ‘act’ such as a clown. A party can easily be overwhelming for an autistic child. However, it might also be an opportunity for them to relax, not have work demands and share some of their favourite music or dance moves!

What to do:

- Write a social story about what will happen at the party and what they can do to prepare for it. Explain that they can wear different clothes to school and that’s ok. Make sure parents have a copy to read at home.

- Put the party date and how long it will last on a calendar in the classroom and have one at home too.

- Let them choose some music to play, and if they feel more comfortable, give them the job of being DJ.

- Make sure there is a quiet space for them to go to if things get too much.

- Practice dancing!

- Prepare a ‘buddy group’ of friends before the party to support and help the autistic child on the day.

- Encourage them to bring a favourite toy to the party as a point of comfort.

- Have a sensory area in the party or just outside so they can go to it and have time out whenever they need it. If this means asking a member of staff to keep an eye on them for the party, then arrange that but don’t have them hovering over the child all the time.

FATHER CHRISTMAS/PRESENTS

A strange man, in a strange red suit comes into the room with a big voice calling out “Ho, Ho, Ho!” and then we ask children to go up to him and receive a wrapped up present which they have no idea about what may be inside. Considering your autistic pupil, this may be a terrifying experience for them. They may be ok with it, but understanding how your child may react will be important.

What to do:

- Show the pupil pictures of the actual person who is dressing up as Father Christmas in the outfit they will be wearing. Add this to a social story to explain that this person will be bringing a present for all the children.

- Some children with autism will need to know what will be in the present and it is ok to tell them. Surprises may not be something they can cope with.

- Read the story of St Nicholas to help older children understand why we have Father Christmas.

THE LACK OF NORMAL LESSONS OR ROUTINES

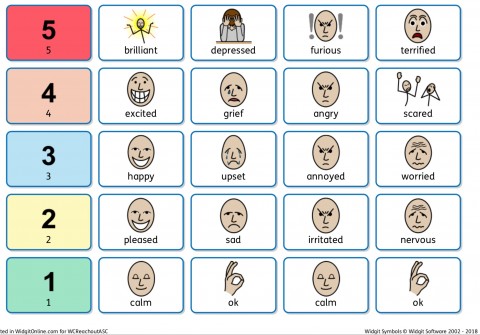

All the things that happen for Christmas are not what we do normally. As the last couple of weeks arrive, everyone is tired, the rest of the children are all excited and the usual routines are often abandoned for play practice, craft or sometimes movies or Christmas colouring sessions. An autistic child may also be tired, overloaded and exhausted through trying to keep up with all the different things that are happening. They may be anxious or over excited about Christmas and be finding it difficult to regulate their emotions and responses.

What to do:

- Please don’t abandon their visual timetable. It will be more important than ever to communicate what is happening and when.

- Consider having more sensory calming breaks so that the child has chance to ‘chill out’ or regulate the sensory overload.

- Have a stack of work they can access that they may prefer to do when others are doing something they find uninteresting or overwhelming.

- Have a box of toys, activities and magazines connected to their special interests that they can access during the less structured times.

THE OUTSIDE WORLD

Just be aware that there is no break from the over stimulation that infects our society in the Christmas season. We are all bombarded by lights, decorations, shiny things, noise, constant repetitive Christmas songs and the anticipation. An autistic child that finds this overwhelming is going to show this in their behaviour. Parents are going to be anxious and will have to try to support their child through this the best they can. Please do speak to parents and ask them how they are ‘doing’ their Christmas. Then you won’t assume things when you talk to their child. For example, if they don’t wrap presents because that will freak out their child, then don’t wrap their class present either.

Here’s a useful link to pass onto parents if they don’t already know about it.

Christmas is really about a little baby that was born to bring hope to the world. No-one was meant to be excluded from that simple message. I hope that in our classrooms we can do all we can to include everyone in what should be a simple and hopeful time of light in the darkest part of the year.

Merry Christmas everyone.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.